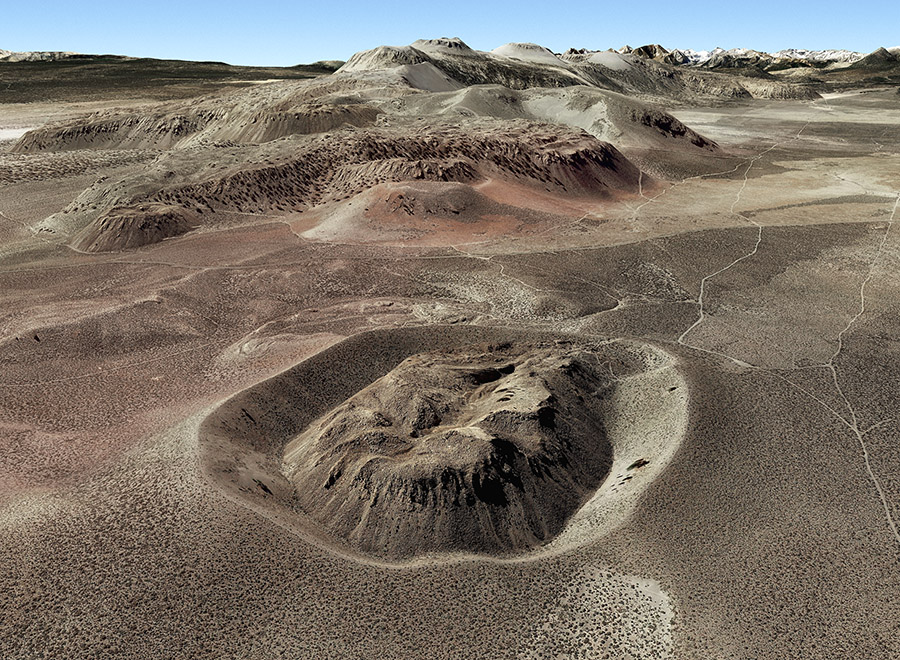

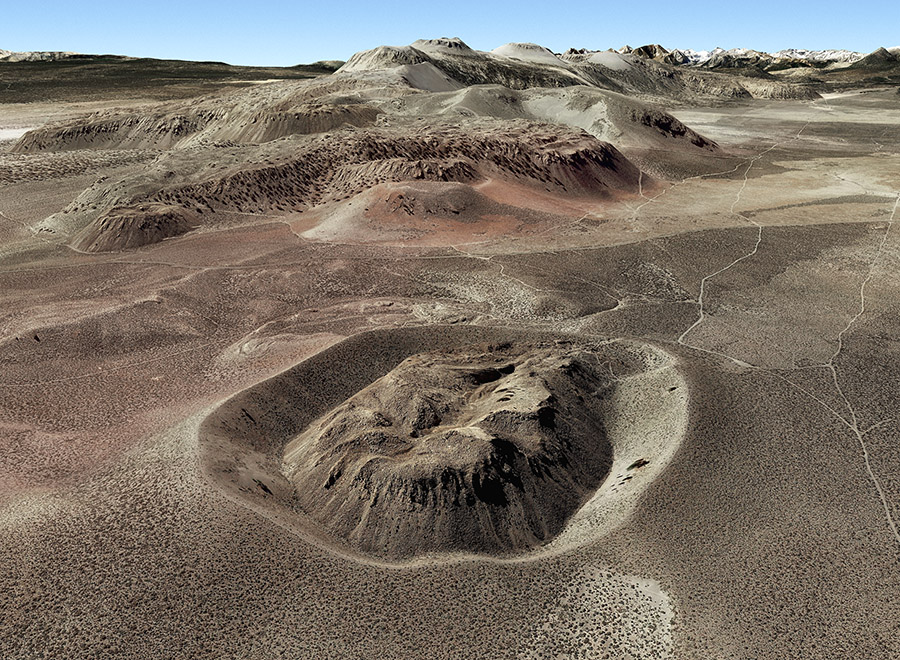

Panum Crater (foreground) and Mono Craters as seen in

Google Earth, looking southeast.

One frosty morning in late October I walked around the narrow rim of Panum Crater, just south of Mono Lake. This is the youngest volcanic feature in the Mono Basin, so if you love landscapes built by fire and carved by ice, I highly recommend this hike, but do it in cool weather or very early on a summer day.

Panum Crater is only about 670 ±20 years old (circa 1320s to 1360s AD) (Sieh and Bursik 1986). The initial eruption was of the “Plinian” type, where abundant gases escape from the rising magma, producing a massive plume and rain of volcanic ash that may continue for weeks. (This is the same type of eruption that occurred on a larger scale at Italy’s Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD, burying Pompeii and Herculaneum—witnessed and later described by Pliny the Younger, hence the name “Plinian.”) After the plumes of gas and ash subsided, magma welled up within Panum Crater to form a jagged dome of obsidian and pumice. Some time after the Panum Crater event, more ash fell throughout the area from eruptions several miles farther south in the Inyo Craters area.

What would it have been like to see, hear, and smell this eruption, to feel the earth shake before and during the eruption? There were certainly Native Americans living here at that time — in the Mono Basin, the Bodie Hills, Bridgeport and Adobe Valleys, and on down to Owens Valley. We don’t know what time of year the eruption occurred, but there could have been groups traveling over Mono Pass and along other routes to trade with neighboring tribes when the eruption began.

Laylander (1998) speculated on how earlier (ca. 880 AD) and larger Plinian eruptions in the Mono Craters may have affected local witnesses: “Local consequences for human populations from the eruption can be imagined. The event may have directly caused some loss of life or frightened the surviving witnesses into leaving the Mono Basin. The decimation of plant and animal communities may have drastically reduced the resource value of the affected area for humans for some time.” (He goes on to consider whether “an occupational hiatus, followed by a return to pre-event conditions” could be detected in the archaeological record and whether the duration of this hiatus could be estimated archaeologically. He concludes that “a hiatus of as much as a century is not likely to be detectable in the archaeological record” using hydration dating of artifacts, unless the sample size is “very large.”)

Banded obsidian and pumice atop the dome.

Panum Crater is not quite the youngest cinder cone in California — that distinction may belong to Cinder Cone in Lassen Volcanic National Park, which erupted about 300 years later, circa 1650. And Lassen Peak itself erupted last in 1915.

References:

Laylander, D. 1998, Cultural Hiatus and Chronological Resolution: Simulating the Mono Craters Eruption of ca. A.D. 880 in the Archaeological Record, Proceedings of the Society for California Archaeology 11:148-154.

Sieh, K. and M. Bursik 1986. Most recent eruption of the Mono Craters, eastern central California. Journal of Geophysical Research, 91(B12): 12,539–12,571.

Copyright © Tim Messick 2020. All rights reserved.

DOWNLOAD THE CHECKLIST