Did you know that Mono County is home to more species of Boechera (“rock-cress,” in the mustard family) than any other county in the United States?

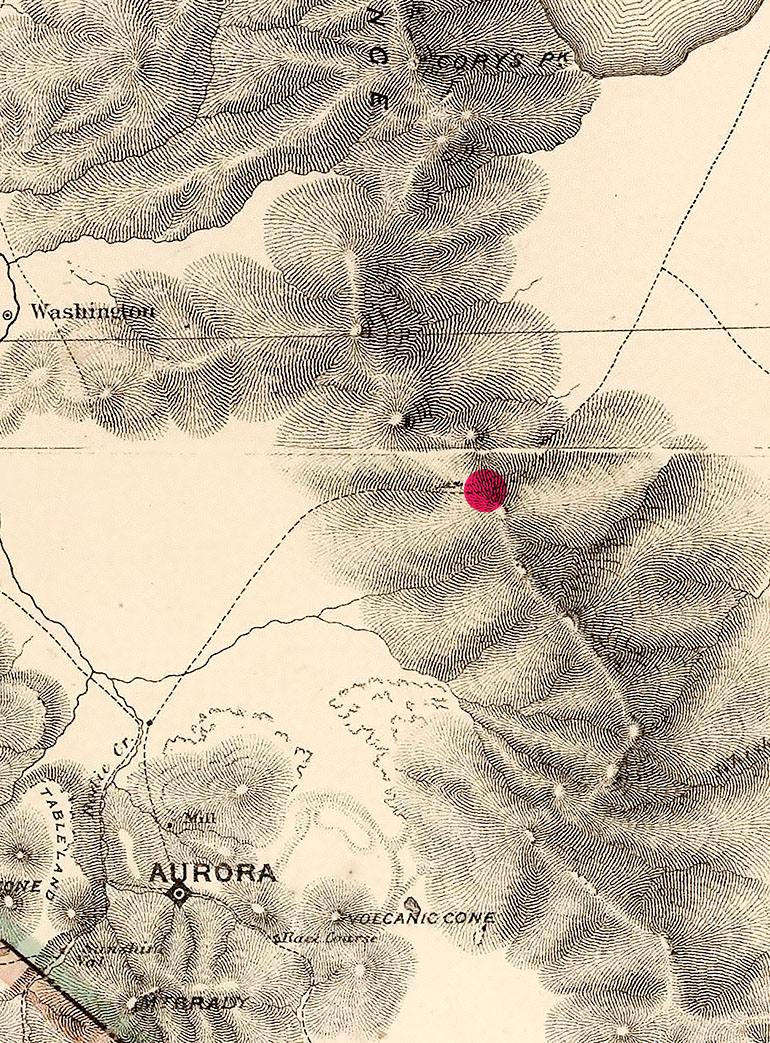

Boechera puberula north of Masonic.

Neither did I, until I ran across a web page with 103 maps showing the number of species per county for the “Largest Genera in Continental North America”. This analysis is part of the Biota of North America Program (BONAP) (Kartesz 2015a, 2015b). The overall distribution patterns these maps reveal are interesting, and perusing the maps for familiar genera and favorite places is also enlightening. For example:

Inyo County, CA boasts the greatest diversity of Eriogonum (55 spp.), Phacelia (43 spp.), Lupinus (40 species), Cryptantha (24 spp.), and Ericameria (24 spp.).

San Bernardino County, CA has the greatest variety of Mentselia (24 spp.), Gilia (23 spp.), and Galium (20 spp.).

Garfield County, UT has the greatest numbers of Astragalus (59 spp.), Penstemon (31 spp.), Oreocarya (16 spp.), and Cymopterus (11 spp.).

Juncus is most diverse in Plumas County, CA (33 spp.).

Castilleja is most diverse in Fresno County, CA (21 spp.).

Artemisia is most diverse in Fremont County, WY (18 spp.) and nearly as diverse in Elko County, NV.

Calochortus is most diverse in Kern County, CA (17 spp.).

And so on. As one might expect, the larger and more physiographically diverse counties are favored to have high numbers of species for large genera in the arid western states (e.g., Inyo, San Bernardino, Nye, and Coconino Counties). Perhaps grouping some adjacent small counties together would shift the locations of some hot spots.

Boechera puberula up close.

Mono County, then, is the center of diversity for Boechera, with 36 species (listed below). Sixteen of these are known or appear likely to occur in the Bodie Hills. No wonder I didn’t find them all during my field work 30-some years ago, and no wonder I gave up trying to key all my specimens and shipped them off to Reed C. Rollins (1911–1998), a professor of botany at Harvard University, and the renowned expert on many Cruciferae, including what we then called Arabis. He kindly annotated them all and shortly thereafter cited several of my specimens in describing Arabis bodiensis (now Boechera bodiensis) as a new species from material previously identified as Arabis fernaldiana var. stylosa. Rollins (1982) wrote, “Furthermore, an extensive sampling of Arabis populations of the Bodie Hills by Tim Messick has shown that what we name A. bodiensis below is consistent in its characters and is present on many appropriate sites throughout the area. This adds up to the necessity of recognizing the Bodie Hills material as an undescribed species.”

Boechera sp.at Grover Hot Springs in Alpine County.

The rock cress species are fairly challenging to identify. One often needs flowers (for their color), leaves (for their shapes and trichomes or hairs), intact fruits, and mature seeds to run a specimen successfully through the keys. Most Boechera plants don’t provide all of these parts in good condition all at the same time. One may need to key the same population in both spring and summer (taking notes and photographs) to do the job well. Familiarity and practice make for easier and more reliable identifications in any large group of plants, so the key to getting good with Boechera may be to live in or near Mono County. Or Inyo County, which has nearly as many Boechera species.

Boechera sp. at Travertine Hot Springs

And finally, the elephant in the room is of course: How does one pronounce the name Boechera? “BOH-chera” (long O) appears likely or even obvious to most Americans, but “oe” in Latin names is always pronounced “ee” (long E), as it should be in Oenothera or Oenanthe. So is it BEE-chera? Boechera is named for Tyge W. Boecher (1909–1983), a Danish botanist, evolutionary biologist, plant ecologist, and phytogeographer. But the Danish spelling is Böcher (with an o-umlaut), and this would suggest the “oe” (or ö) should be pronounced more like the “oe” in the French words oeil (eye) and oeuvre (an artist’s collected works). This sound can’t be spelled in English, but “BUH-chera,” with a listless enunciation of the first syllable, comes close. Or maybe “BOO-chera.” Take your pick.

Boechera sp. in Bridgeport Canyon. These are not especially showy plants.

The 36 species of Boechera in Mono County (according to CalFlora) are listed below. Those known or likely to be in the Bodie Hills are followed by a “(BH)”.

- Boechera arcuata (BH)

- Boechera bodiensis (BH)

- Boechera cobrensis (BH)

- Boechera covillei

- Boechera davidsonii

- Boechera depauperata

- Boechera dispar

- Boechera divaricarpa

- Boechera elkoensis (BH)

- Boechera evadens (BH)

- Boechera glaucovalvula

- Boechera howellii

- Boechera inyoensis

- Boechera lemmonii (BH)

- Boechera lyallii (BH)

- Boechera microphylla

- Boechera pauciflora (BH)

- Boechera paupercula (BH)

- Boechera pendulina

- Boechera pendulocarpa (BH)

- Boechera perennans

- Boechera pinetorum

- Boechera pinzliae

- Boechera platysperma (BH)

- Boechera puberula (BH)

- Boechera pulchra (BH)

- Boechera rectissima

- Boechera repanda

- Boechera retrofracta (BH)

- Boechera shockleyi

- Boechera sparsiflora (BH)

- Boechera stricta (BH)

- Boechera suffrutescens

- Boechera tiehmii

- Boechera tularensis

- Boechera xylopoda

References:

Kartesz, J.T., The Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2015a. North American Plant Atlas. (http://bonap.net/napa). Chapel Hill, N.C.

Kartesz, J.T. 2015b. Floristic Synthesis of North America, Version 1.0. Biota of North America Program (BONAP) [maps]

Rollins, Reed C. 1982. Studies on Arabis (Cruciferae) of Western North America II. Contributions from the Gray Herbarium. 212: 103-114.

Boechera becomes infected with the yellow, flower-mimicing Puccinia rust. (See the Puccinia post.)

Copyright © Tim Messick 2016. All rights reserved.

DOWNLOAD THE CHECKLIST