Back in March 2023, I did a presentation for the Nevada Native Plant Society on plants of the Bodie Hills. One small part of that presentation was a review of the history of botanical collecting, and more recently, iNaturalist observations of plants, in the Bodie Hills. It was an interesting topic to research, so what follows is an expanded summary of my findings, along with some charts and maps.

Collections of Plant Specimens in Herbaria

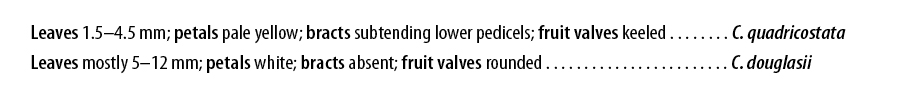

I compiled a list of all plant collections in the Bodie Hills using search tools of the Consortium of California Herbaria (CCH). Their CCH2 portal serves data from all specimens (vascular and nonvascular, in California and beyond) housed in all 55 CCH member herbaria. These data portals allow anyone to search digitized records of herbarium specimens in a variety of ways. Because about a third of the Bodie Hills is in Nevada, and CCH2 data are not restricted to California, I used the CCH2 portal to find and download records of 4,268 plant collections throughout the Bodie Hills from 1866 through 2021.

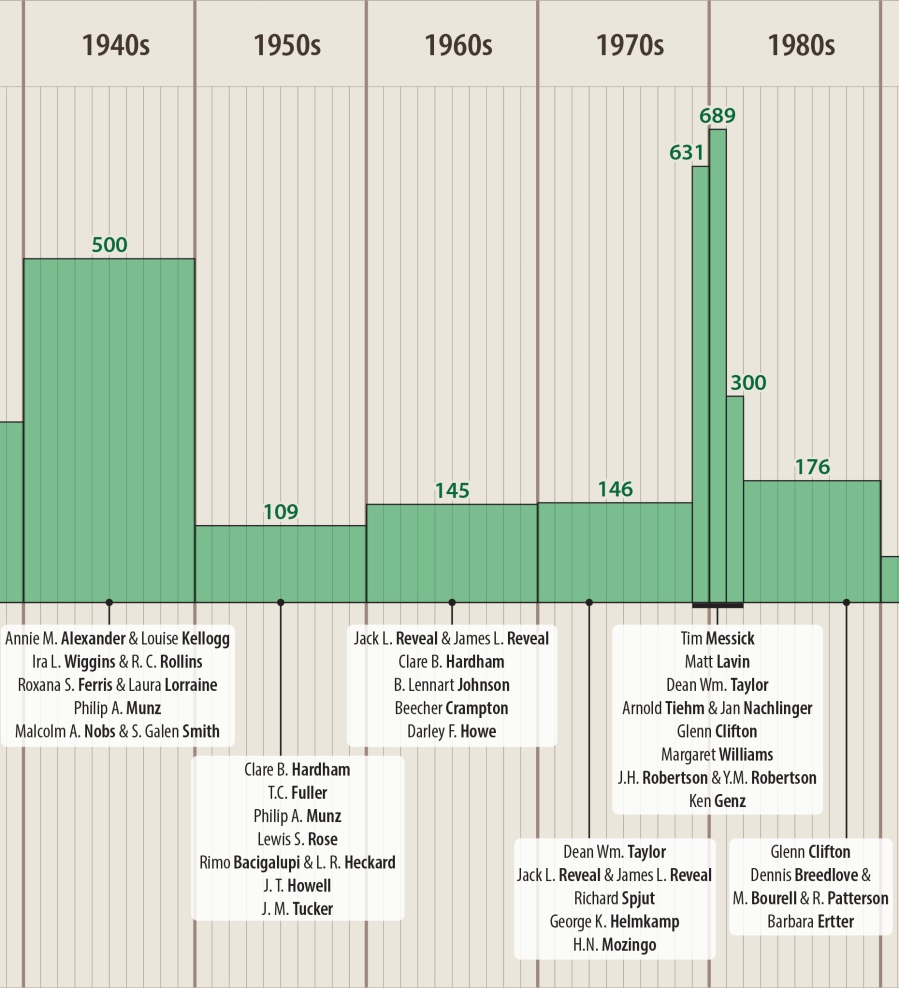

Here, then, is a timeline (below), summarizing the number of herbarium specimens collected over various periods of time. Below each of the green bars are the names of botanists who collected the most during those periods.

The timeline above may appear too small to read on your screen, so below I’ve divided the same thing into three larger sections.

The earliest collections listed were of Ericameria nauseosa and Sphaeralcea ambigua by Henry Bolander in 1866. The locations were recorded as simply “near Bridgeport,” so these may not have been exactly in the Bodie Hills. Bolander was an energetic collector while he was California State Botanist, 1864–1873 (and later, State Superintendent of Public Instruction, then San Francisco Superintendent of Schools).

Thirty-two years later, in 1898, Joseph Congdon collected Atriplex canescens, Opuntia polyacantha, and probably also Artemisia nova along a what he called the “Mono to Bodie (Desert Road)” and a “side-road between Goat Ranch and Bridgeport.” I believe these were along what is now Coyote Springs Road in Bridgeport Canyon. This was for many years the main route from Mono Basin to Bridgeport, before roads were established over Conway Summit. Congdon was a lawyer who lived in Mariposa, 1882–1905, and contributed significantly to early botanical exploration, particularly in the Yosemite region.

Harvey Monroe Hall made at least 7 collections in the hills between Mono Basin and Bridgeport in 1918, 1921, and 1925. Hall at that time worked at the Carnegie Institution Division of Plant Sciences at Stanford University; throughout his life he collected over 200,000 specimens. Philip A. Munz made a few collections in the same area in 1928. Munz was then a young professor of botany at Pomona College. Decades later, Munz and David Keck authored A California Flora (UC Press 1959), which became a standard reference for identifying California plants for more than 30 years.

Botanical collecting took a leap forward and across the state line in 1929, when “Mrs. John D. Wright” collected at least 29 specimens around Aurora. Ysabel Galban Wright, born in Cuba in 1885, married John Dutton Wright (founder of the Wright Oral School for the Deaf in New York City, where Helen Keller was an early student) in 1912. The couple relocated to Santa Barbara about 1919, where Ysabel became an avid gardener with a special interest in cacti and California native plants. She visited Aurora during a botanical collecting trip that also included Mono and Tuolumne counties in 1929.

During the 1930s several botanists collected in the area, notably Carl B. Wolf (Botanist at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 1930–1945), and G. A. Graham and T. M. Hendrix (both collecting and documenting vegetation in 1937 for what was then Mono National Forest).

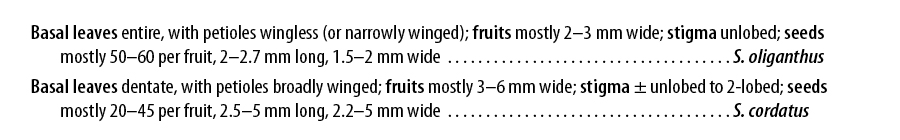

In the 1940s, additional names familiar to California botanists appear in the list, including Annie Alexander & Louise Kellogg, Ira Wiggins & Reed Rollins, Roxanna Ferris & Laura Lorraine, and again, Philip Munz (who took a particular interest in the flora at Travertine Hot Springs). It was in the summer of 1945 that Wiggins & Rollins collected type specimens of both Streptanthus oliganthus (Masonic Mountain jewelflower) and Boechera bodiensis (Bodie Hills rock-cress). Also in the summer of ’45, Alexander & Kellogg collected type specimens of Cusickiella quadricostata (Bodie Hills Cusickiella) and Phacelia monoensis (Mono County Phacelia). Others collecting here during the ’40s included C. Leo Hitchcock, Robert F. Hoover, Beecher Crampton, and Malcolm A. Nobs & S. Galen Smith.

During the 1950s, Philip Munz visited the Chemung Mine area. Thomas C. Fuller (Plant Taxonomist for the California Department of Food and Agriculture) collected along the west side of the Bodie Hills. Clare B. Hardham collected along the Bodie-Masonic Road near Potato Peak.

In the 1960s, Jack Reveal (forest ranger) and his son James L. Reveal (renowned Eriogonum taxonomist and professor) collected in the area. Clare Hardham again visited the Rough Creek/Potato Peak area, and Masonic Mountain. Darley F. Howe collected near Bodie.

During the 1970s, Dean Taylor collected extensively throughout the Mono Basin and surrounding areas. Other collectors included Dennis Breedlove, Glenn Clifton, Ken Genz, and George K. Helmkamp (chemistry professor at UC Riverside). A spike in collecting occurred in 1979, because that’s when I arrived on the scene, collecting for my MA thesis (a local flora of the Bodie Hills) at Humboldt State University. I continued collecting for that project in 1980-81.

During the early 1980s, Matt Lavin, then a graduate student at UNR, collected extensively in the northern Bodie Hills for his floristic study of the upper Walker River watershed. Others active in the ’80s included Arnold (Jerry) Tiehm (Herbarium Curator at University of Nevada Reno) and Jan Nachlinger (plant ecologist), Dennis Breedlove, Glenn Clifton, Mary DeDecker, Barbara Ertter, and Hugh Mozingo (author of Shrubs of the Great Basin: A Natural History).

During the 1990s and 2000s there was less collecting in the Bodie Hills, though Tom Schewich and others were quite active in and around the Mono Basin.

In the 2010s Ann Howald started collecting intensively throughout Mono County, including the Bodie Hills. Jerry Tiehm and Jan Nachlinger made more visits to the Nevada side of the range. In recent years, Ann Howald (preparing a Flora of Mono County) and James André (of the Granite Mountains Desert Research Center) have been the most active collectors in the Bodie Hills.

In summary, my search produced a list of about 4,268 specimens from the Bodie Hills, collected from 1866 to 2021. I say “about”, because a few were probably collected outside the area but their locations were mis-mapped or misinterpreted as being within the Bodie Hills (erring on the side of too many specimens). On the other hand, some specimens probably exist that have not been digitized and georeferenced, or reside in herbaria that are outside the scope of CCH2 (erring on the side of too few specimens). Also, the search area boundary is a bit arbitrary in some areas and can be adjusted to include more or fewer collections.

Much more interesting than the exact number, though, is to see the names of people who have collected there, if only briefly, over the decades. Many of them became well known for their contributions to western American botany.

You can generate an updated search, and change the boundaries or other search criteria if you wish, HERE.

Observations of Plants on iNaturalist

Several years ago an ambitious citizen science project called iNaturalist came on the scene, providing me and many others with a different way to document biodiversity—by uploading photographs of identifiable species, along with location, date/time, and sometimes other metadata for each observation. There are many caveats to consider in assessing the quality and value of any particular set of iNaturalist data, but on the whole, it’s an effective way for anyone from casual, curious non-specialists to seasoned professional biologists to quickly share observations, get feedback, and learn from what others have posted. Physical specimens enable types of research that cannot be done from photographs alone, but I think iNaturalist provides a useful compliment to traditional herbarium-based collections.

The timeline below shows plant observations in the Bodie Hills posted to iNaturalist, by year, from 2012 through 2022. In the background, for comparison, are the numbers of herbarium specimens from the charts above. The number of observations is growing rapidly. Many of these observations are mine, but certainly not all, and some very noteworthy observations (documenting species neither collected nor observed previously in the Bodie Hills) have been posted by others.

You can generate an updated search in iNaturalist, and revise the search criteria if you wish, HERE.

Locations of Collections and Observations

The maps below show you that both collections and observations have been concentrated along (1) roads that provide relatively easy access and (2) other popular areas to visit in the Bodie Hills.

Little or no collecting or observing has occurred in some other areas. These are among the more remote and difficult-to-access corners of the Bodie Hills. Such areas include:

• Mount Hicks and Spring Peak

• Aurora Crater

• Bald Peak

• Southeast perimeter of the Bodie Hills

• Atastra Creek and the middle reaches of Rough Creek

• Masonic Gulch north of Masonic Lower Town

• Aspen groves south of upper Aurora Canyon

• Big Alkali

Treks into these remote areas could be rewarded with interesting discoveries!

Townsendia scapigera

Copyright © Tim Messick 2023. All rights reserved.