Anyone hiking in the Sierra Nevada eventually encounters Eriogonum wrightii (“Wright’s buckwheat” or, if you must, “Bastard sage”). The common form through most of the high Sierra is variety subscaposum—a short, more or less matted, perennial subshrub, with stems bearing white to pink flowers ascending either from throughout the plant, or often from just around its perimeter. It’s found in the Bodie Hills too, often on moderate to steep scree-like slopes.

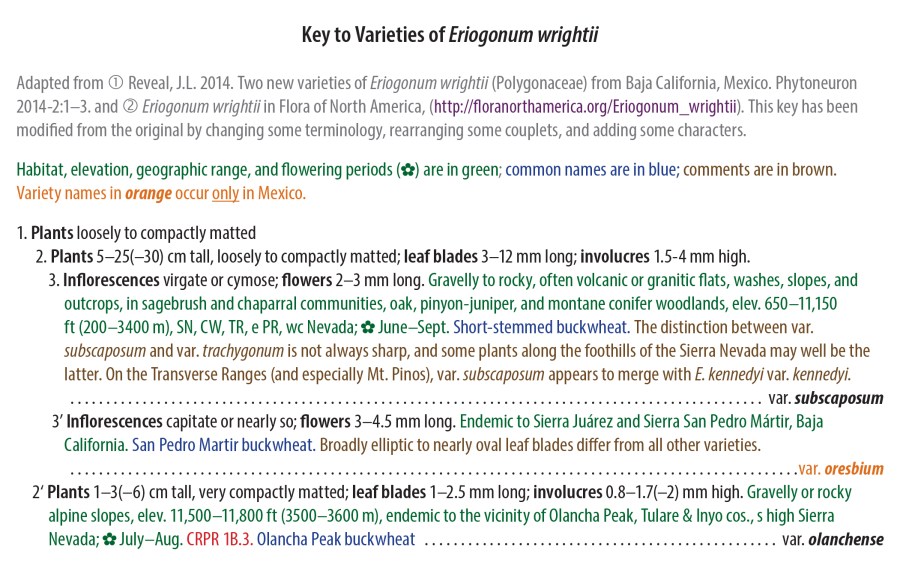

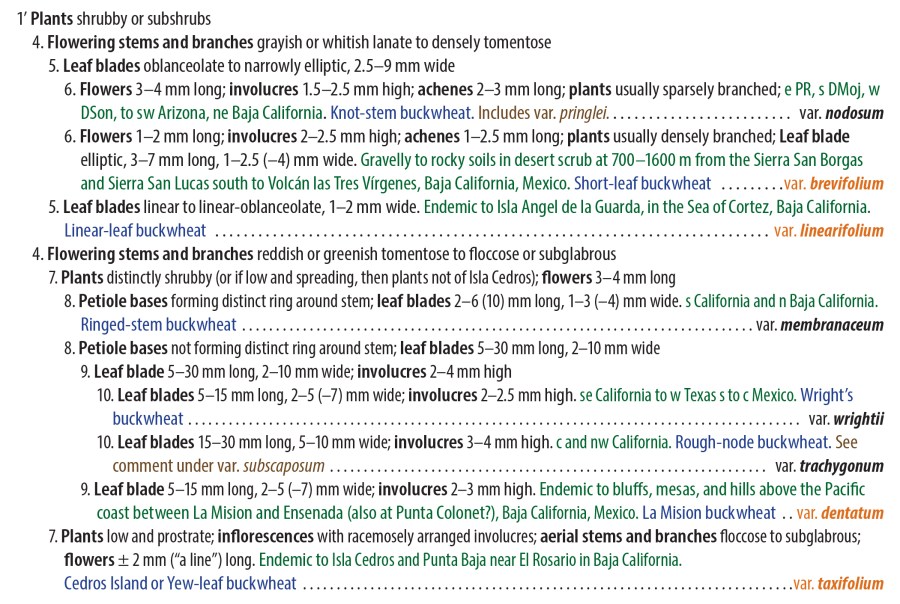

Eriogonum wrightii has 11 varieties in all: 5 occur only in Mexico (mostly in Baja California); the rest occur in the United States, but at least 3 of these extend across the southern border (and have certainly done so since long before there ever was a border). Most plants will run through the key without much difficulty, and some varieties are largely separate from the others geographically. Where taxon ranges may overlap, only 2 or 3 varieties will vie for your attention.

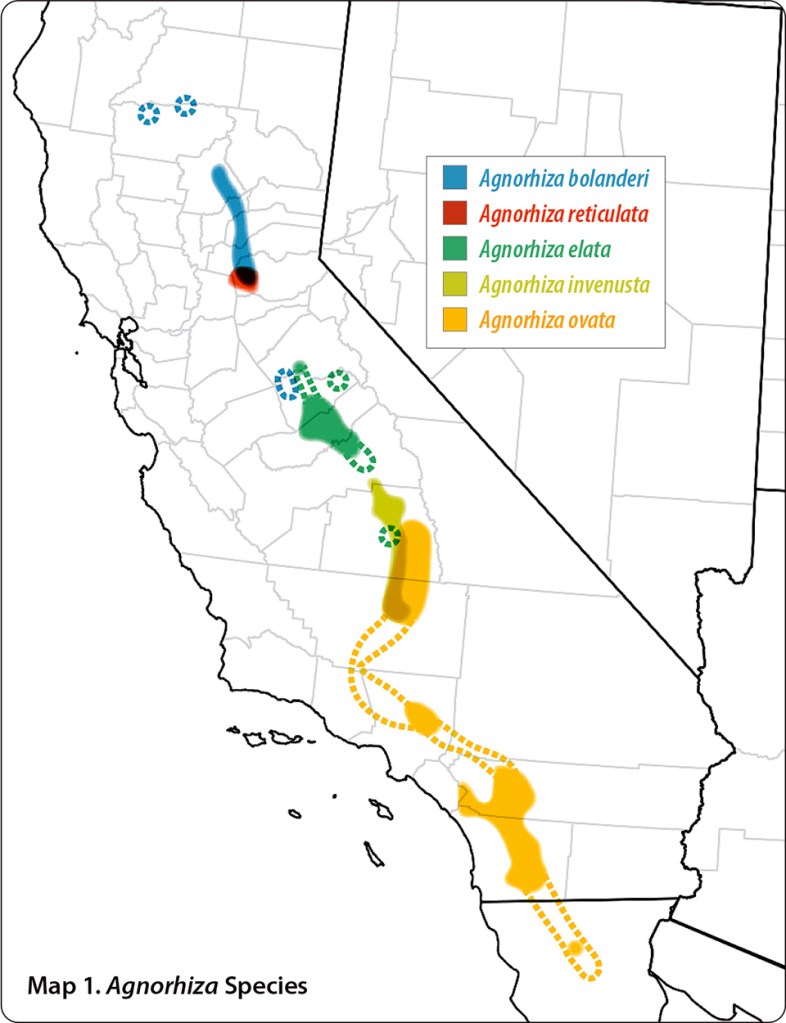

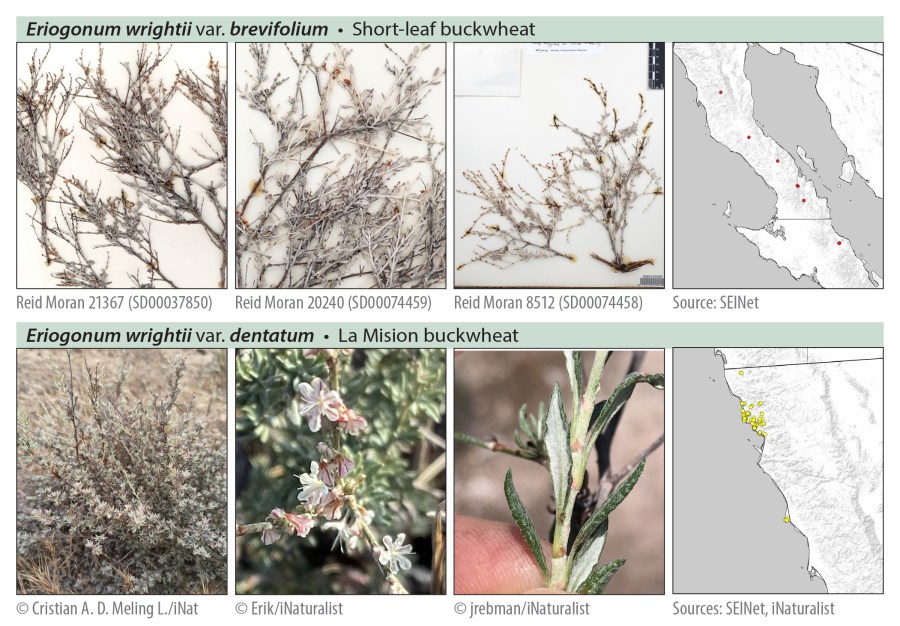

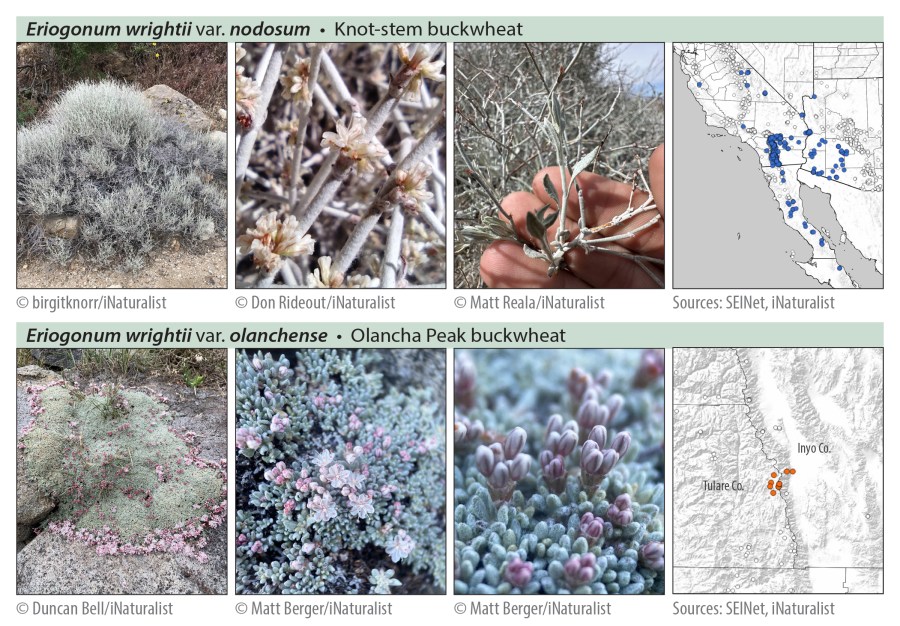

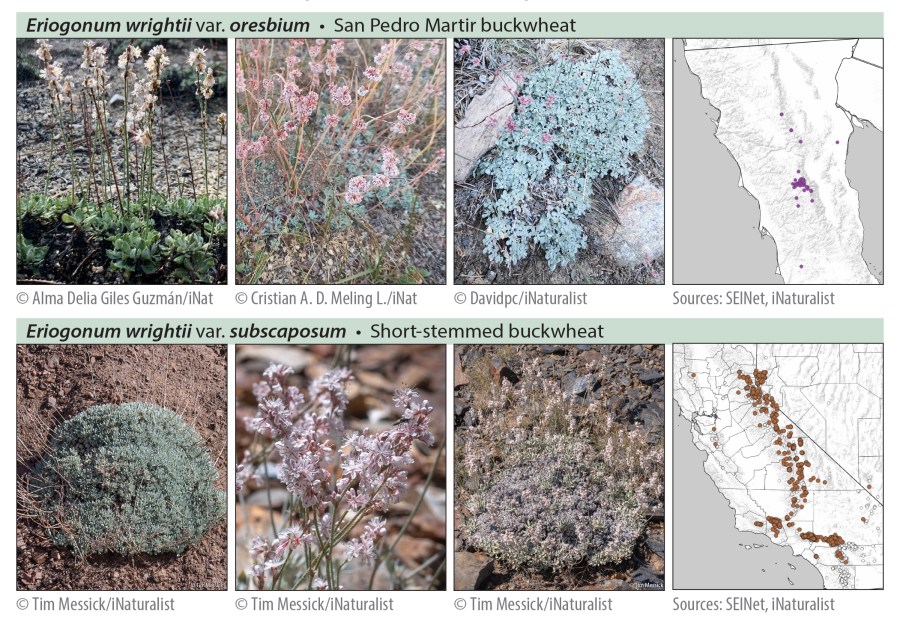

Curious to learn more about the other 10 varieties of E. wrightii and their distribution, I mapped all 11 using herbarium and iNaturalist data. The range maps were produced in QGIS, based on specimen location data in the SEINet Portal Network and iNaturalist observations (“Research Grade” only) as of December 11, 2023. NOTE: Some dots on the maps may be based on misidentifications or mismapped coordinates; most individual data points have not been reviewed to eliminate such errors, so taxon ranges indicated by these maps should be considered approximate.

I also wrote a key, adapted from Reveal 2005 and Reveal 2014. This key has been modified from the originals by changing some of the terminology, rearranging some couplets, and adding some characters. I like my keys to include some of the information traditionally provided separately in descriptions, and I like to use text color to visually “layer” different categories of information. This is what you get when a botanist takes up information design and learns to love Adobe InDesign software.

The photos below are all from iNaturalist, except for a few from herbarium specimens of rarely observed taxa. All the photos are licensed for non-commercial use by the copyright holders under Creative Commons licenses CC BY 4.0, CC BY-NC 4.0, or CC BY-NCND 4.0. Thank you to all the photographers for allowing these images to be used!

References

- iNaturalist search results for “research grade” observations of Eriogonum wrightii, accessed 11 December 2023. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&quality_grade=research&taxon_id=59243

- Reveal, J.L. 2005. Eriogonum wrightii in Flora of North America, Volume 5, http://floranorthamerica.org/Eriogonum_wrightii, accessed 11 December 2023.

- Reveal, J.L. 2014. Two new varieties of Eriogonum wrightii (Polygonaceae) from Baja California, Mexico. Phytoneuron 2014-2: 1–3. https://www.phytoneuron.net/2014-publications/

- SEINet search results for Eriogonum wrightii, accessed 11 December 2023. https://swbiodiversity.org/seinet/collections/list.php?taxa=Eriogonum%20wrightii&usethes=1&taxontype=2

Copyright © Tim Messick 2024. All rights reserved.