A travertine ridge at Travertine Hot Springs (Sierra Nevada in the background).

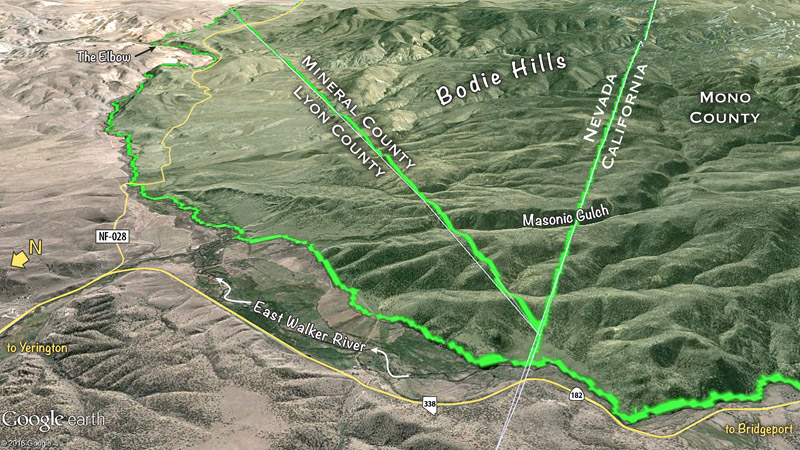

Philip A. Munz (1892–1974) is a name well known to generations of California botanists. In the 1950s he collaborated with David Keck to write A California Flora, published in 1959 by the University of California Press. A decade later Munz compiled the Supplement to A California Flora (1968), and in 1973, U.C. Press published the combined volume A California Flora and Supplement. This is the 1,900-page book I carried with me on most of my plant collecting forays in the Bodie Hills, beginning in 1978. This is the book in which I keyed most of my collections for many years.

Munz visited the Bodie Hills several times from 1928 to 1960. He seems to have found Travertine Hot Springs, a mile southeast of Bridgeport, an especially interesting place to collect. According to my geographic search of herbarium specimens using Calflora, he collected at Travertine Hot Springs on:

- 21 May, 1947 (18 specimens)

- 16 June 1949 (67 specimens)

- 28 July 1950 (20 specimens)

- 12 September 1960 (12 specimens)

He also collected 36 specimens in the Masonic Mountain area on 20 July, 1955, plus several more along Virginia Creek near the confluence with Clearwater Creek in June 1928 and May 1947.

One of the wet meadow areas at Travertine Hot Springs.

Some of the plants Munz collected at Travertine Hot Springs more than a half-century ago have not been documented by subsequent visitors to the area (including me, during my 1978-81 visits), as far as I can determine from my searches of herbarium databases. I doubt the plants have gone away—but to find them—especially the annuals—you need to be in the right place at the right time during a favorable year, and you need to be looking and paying attention. Most visitors to Travertine are focused on taking dip in the springs. Still, it would be great to confirm the continued presence of the plants Munz found here.

So here’s a challenge for interested field botanists: Before or after immersing yourself in a pool of hot water, look for the following plants at Travertine Hot Springs, note their location, and please let me know if you find them:

DICOTS

ASTERACEAE: Crepis runcinata subsp. hallii (Hall’s meadow hawksbeard), “Wet alkaline flats and meadows.”

BORAGINACEAE: Cryptantha gracilis (Slender cryptantha), “On disintegrated travertine.”

BORAGINACEAE: Cryptantha scoparia (Gray cryptantha), “Abundant in dry loose disintegrated travertine.”

PLANTAGINACEAE: Antirrhinum kingii (King’s snapdragon), “Abundant in dry loose disintegrated travertine; pinyon-juniper woodland.”

POLEMONIACEAE: Aliciella humillima (Smallest aliciella), “Abundant in dry loose disintegrated travertine; pinyon-juniper woodland.”

POLEMONIACEAE: Aliciella leptomeria (Sand aliciella), “Hot springs, in dry loose disintegrated travertine, pinyon-juniper woodland.”

POLEMONIACEAE: Gilia ophthalmoides (Eyed gilia), “loose dry disintegrated travertine.”

POLEMONIACEAE: Ipomopsis polycladon (Branching gilia), “Disintegrated travertine.”

POLYGONACEAE: Eriogonum hookeri (Hooker’s buckwheat), “Infrequent annual on sunny, dry, loose, alkaline soil.”

POLYGONACEAE: Eriogonum ovalifolium var. purpureum (Purple cushion wild buckwheat), “Crevices in travertine deposit.”

MONOCOTS

ALLIACEAE: Allium atrorubens var. cristatum (Crested onion, Inyo onion), “Dry volcanic heavy soil, wet in early season.”

LILIACEAE: Calochortus excavatus (Inyo County star tulip), “Infrequent on dry disintegrated travertine. More common in nearby volcanic soil.”

POACEAE: Elymus multisetus (Big squirreltail), “along foot of travertine ridge.”

On a recent visit to Travertine Hot Springs (early June 2016), I did run into a population of Symphoricarpos longiflorus (Desert snowberry), collected here by Munz in 1949. Here it is, along with some of the other cool plants I saw during the same visit:

Symphoricarpos longiflorus (Desert snowberry)

Another Symphoricarpos longiflorus with paler corollas

Penstemon speciosus (Showy penstemon)

Packera multilobata (Lobeleaf groundsel)

Cleomella parviflora (Slender cleomella)

Minuartia nuttallii var. gracilis (Nuttall’s sandwort)

Triglochin maritima (Common arrow-grass)

Copyright © Tim Messick 2016. All rights reserved.

DOWNLOAD THE CHECKLIST

Plants of the Bodie Hills, an Annotated Checklist is a free, 47-page PDF document (5.1 MB),

Plants of the Bodie Hills, an Annotated Checklist is a free, 47-page PDF document (5.1 MB),