I need your help—those of you who live somewhat close to the Bodie Hills. Three plants have yet to be identified there because they have not been seen up close, photographed clearly, or observed under the right conditions for identification. Since my home is a nearly 5-hour drive from their locations, I don’t know when I might be in the right places at the right times to identify these plants. So, I invite anyone who is interested to do a bit of “citizen science” botanical field work and post the observations on iNaturalist. Details follow.

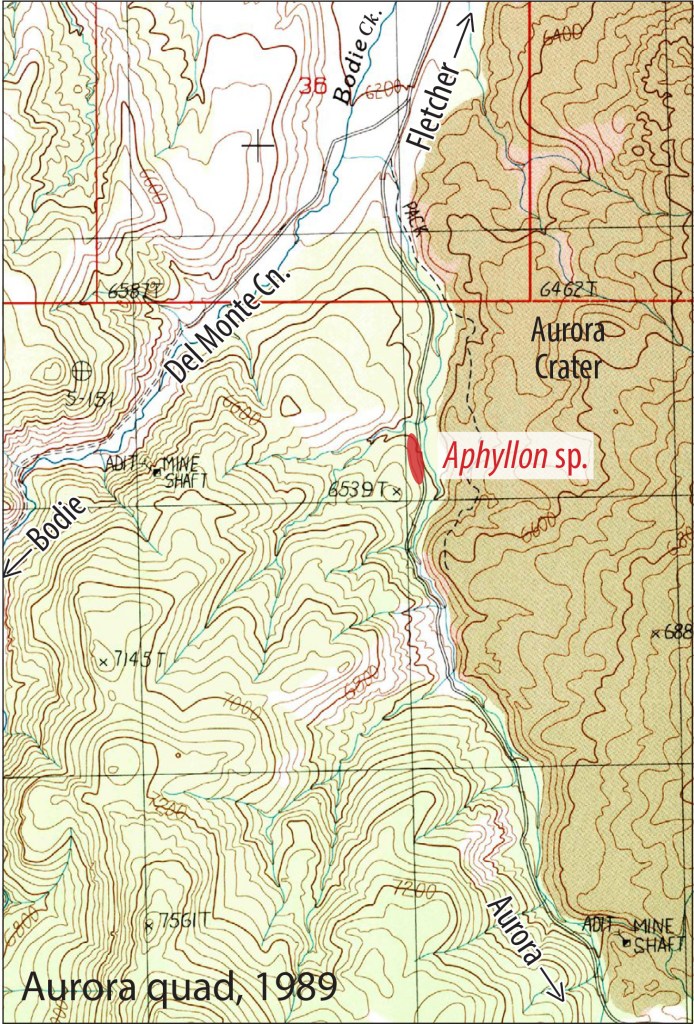

Mystery Plant #1: An Aphyllon Near Aurora

This plant has been observed twice, in June 2021 and April 2022 at the base of a road cut along the road to Aurora (Mineral County, Nevada), about 0.85 mile south of the intersection with the road through Del Monte Canyon to Bodie (elevation about 6,400 feet). Both times the plants were well past flowering, dried out and crumbling to the point where critical features for identifying the species were no longer present.

When might these plants be in fresh, identifiable condition? Similar plants have been observed in Adobe Valley southeast of Mono Lake (Mono County, CA)(elevation about 6,500 feet). Plants in that area appear to have been in good condition during July. The plants in the photos above had probably flowered during the previous summer.

This plant is clearly in the genus Aphyllon (Broomrapes) of Orobanchaceae (Broomrape family). They are parasites. Lacking chlorophyll, they derive sugars and other nutrients needed for growth from the root systems of nearby shrubs, often sagebrush or rabbitbrush. The inflorescence emerges directly from the ground. It tends to be mostly purplish, yellowish, or brownish in color, with the corollas various combinations of purple, pink, yellow, and white. A taxonomic note: All Broomrapes in North America (about 17 species) were formerly in Orobanche, before that genus was split mid-Atlantic, with all the New World Broomrapes placed in genus Aphyllon and all Old World species remaining in Orobanche (see PhytoKeys 75: 107–118 for an explanation).

Our mystery plant also clearly has an elongate above-ground stem that bears flowers on short pedicels, as in Aphyllon parishii and several other species. In some other species the flowers emerge on much longer pedicels from a very short, below-ground stem—which is the case in two other species of Aphyllon found in the Bodie Hills: A. corymbosum and A. fasciculatum.

The Aphyllon observations in Adobe Valley have been difficult to identify and it’s been speculated (here and here) that an undescribed taxon may be lurking in that area. Could the Aphyllon near Aurora fit into this potentially new taxon also? Photographs showing details of flowers, bracts, and stem are needed.

Mystery Plant #2: A Silene Near Cow Camp Road

This plant is definitely in Caryophyllaceae (Pink family); I think it’s a Silene (because of the notched petals), maybe Silene nuda (Sticky catchfly). But in these photos that came to me by way of the Eastern Sierra Land Trust, from someone wanting to identify it, the image resolution is just a bit too low for a confident identification, so it needs to be revisited in the field. This was seen (in early August, 2019) in the central Bodie Hills, roughly mid-way between Cow Camp Road and Rough Creek, a little north of “Halfway Camp”, elevation about 7650 feet.

Another tall, perennial Silene reported to occur in the eastern Sierra is S. verecunda (San Francisco campion). In Silene nuda, the pedicel and calyx are glandular-puberulent to glandular-hairy. In Silene verecunda, the pedicel and calyx are puberulent (short-hairy), but not glandular. Photos of the plants should therefore include close-ups of the flower, calyx, and pedicel. Clear views of the basal and cauline leaves (showing shape, hairiness, and relative size) would be helpful as well.

The nearest collection of Silene nuda is in Douglas County near Topaz Lake. The species occurs in the northern Sierra Nevada—mostly north of Tahoe—to south-central and southeast Oregon, southern Idaho and across northern and central Nevada. If confirmed here, the Bodie Hills would be the southwestern-most known occurrence of Silene nuda.

A map of Silene nuda collections (sources: CCH2 and IRHN)

Mystery Plant #3. A Pine Near Millersville

High on a remote mountain slope 1.2 miles north-northwest of Potato Peak, above the head of a steep gully at 9,540 feet, and surrounded by thickets of mountain-mahogany, is a small stand of pines. But which one? I think they’re most likely Limber pines (Pinus flexilis), because that’s what occurs at a similar elevation on the north slope of Bodie Mountain, but Lodgepole pines (Pinus contorta subsp. murrayana) occur in scattered, mostly small stands in the central Bodie Hills too. A much closer look at these pines is needed, ideally documenting their overall appearance, the number of needles per fascicle, and the size and appearance of the cones.

Viewed from far down in Aurora Canyon, the details needed for a confident identification are not visible. This stand of pines is a little north of the site of Millersville (topic of an earlier post).

Copyright © Tim Messick 2023. All rights reserved.