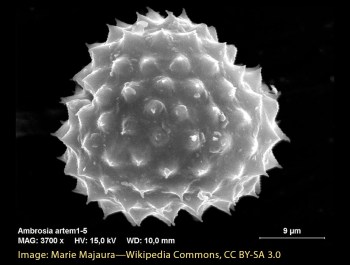

Recently I found myself looking closely at keys, descriptions, and photos of Psathyrotes annua (Annual turtleback) and P. ramosissima (“regular” Turtleback)—both rayless members of the Sunflower family, Asteraceae—to clear up some lingering uncertainty over how to distinguish the two. Then one taxon led to another and it became a larger project.

Psatyrotes annua is familiar to many who have wandered the perimeter of Mono Lake. It thrives in the sparsely vegetated sands and gravelly pumice of Mono’s prehistoric and post-1945 receding shorelines. It’s often misidentified as P. ramosissima, which so far, has probably not been found in the Mono Basin, but is common in the Mojave, Colorado, and western Sonoran Deserts. These two can be distinguished as follows:

- Leaf blades generally clearly divided by deeply-set, anastomosing (cross-connecting) veins into irregular, ovate to polygonal areas (suggesting the segmented “scutes” of a turtle’s carapace); outer phyllaries ± wide, spatulate to obovate, widely spreading to reflexed; florets 21–26 (16–32) per head; pappus of 120–140 bristles in 3–4 series …… Psathyrotes ramosissima

- Leaf blades generally weakly or not at all divided by veins into scute-like areas; outer phyllaries ± narrow, mostly lance-linear, ± erect to spreading; florets 13–16 (10–20) per head; pappus of 35–50 bristles in one series …… Psathyrotes annua

Left: © Chloe & Trevor Van Loon/iNaturalist, Right: © Tom Chester/iNaturalist

Left: © Tim Messick/iNaturalist, Right: © Jim Morefield/iNaturalist

Exploring this small genus further, one finds there are currently three species in Psathyrotes, another close relative formerly in Psathyrotes now banished to Trichoptilium—a monotypic (one species) genus—and three more close relatives housed in Psathyrotopsis, a newer genus carved out of Psathyrotes.

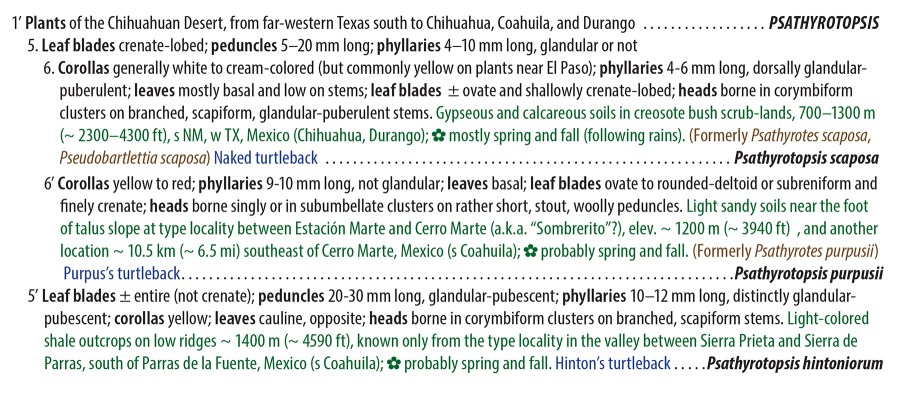

Apparently no single key has been crafted that includes all 7 species of Psathyrotes, Trichoptilium, and Psathyrotopsis. The Jepson eFlora includes two Psathyrotes and the Trichoptilium. The Flora of North America (FNA) includes all three Psathyrotes, the Trichoptilium and one species of Psathyrotopsis, but not the other two, which appear to be narrow endemics in southern Coahuila, Mexico. Both Jepson and FNA make you work through ponderous keys for the entire sunflower family to distinguish these three genera. A paper on “Taxonomy of Psathyrotes” (Strother and Pilz 1975) includes a key to all of the taxa included in FNA, but not the third Psathyrotopsis, because it was described later (Turner 1993).

So, why not write a straightforward key that includes all seven taxa? Not so simple, it turns out, because existing keys don’t all use the same set of characters, and that newest species endemic to southern Coahuila (Psathyrotopsis hintoniorum) has never been included in a key with its relatives—and the paper describing it refers the reader to the formal description in Latin to figure out what distinguishes it from Psathyrotopsis purpusii. Thank goodness for Google Translate!

Below is an image of my key. (The very limited text formatting abilities in this WordPress blog don’t lend themselves to an indented key longer than 1 or 2 couplets.) The key is adapted from Baldwin 2012, Strother 2006a, Strother 2006b, Strother and Pilz 1975, and Turner 1973 (citations below). It has been modified from the originals by adding species, changing some terminology, rearranging some couplets, and adding some character states.

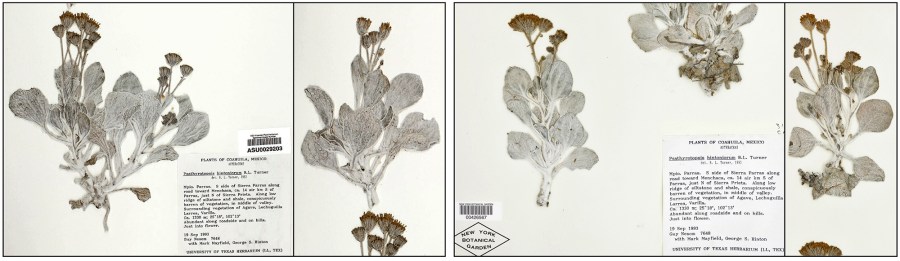

Here are photos of the rest of the species in Psathyrotes, Psathyrotopsis, and Trichoptilium (thank you to the iNaturalist contributors who allow their images to be used non-commercially!)

Left: © Arizona State University, Right: © New York Botanical Garden

(both are duplicate sheets of Guy Nesom 7648)

Left: © Matt Reala/iNaturalist, Right: © Joey Santore/iNaturalist

Left: © Jessica Irwin/iNaturalist, Right: © Irene/iNaturalist

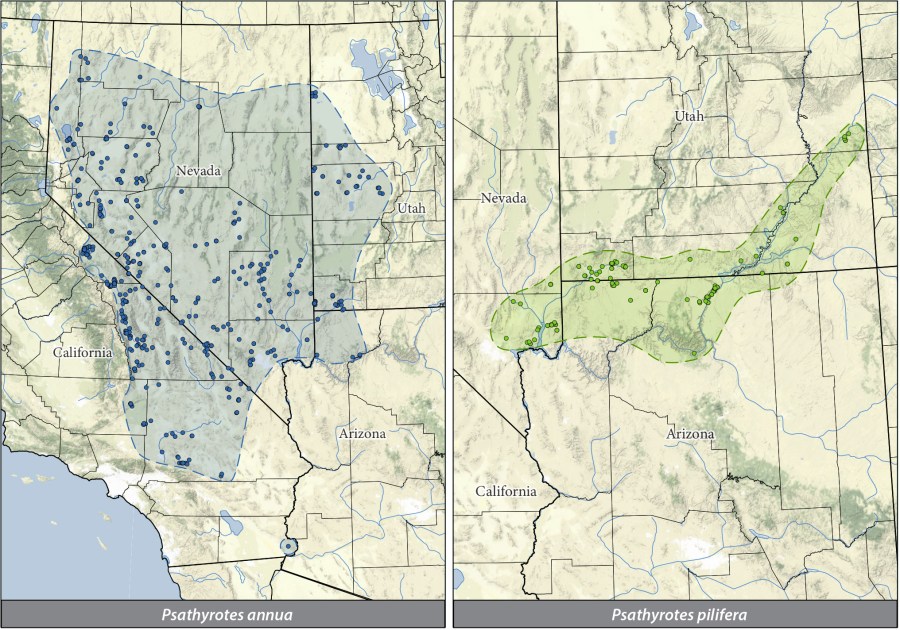

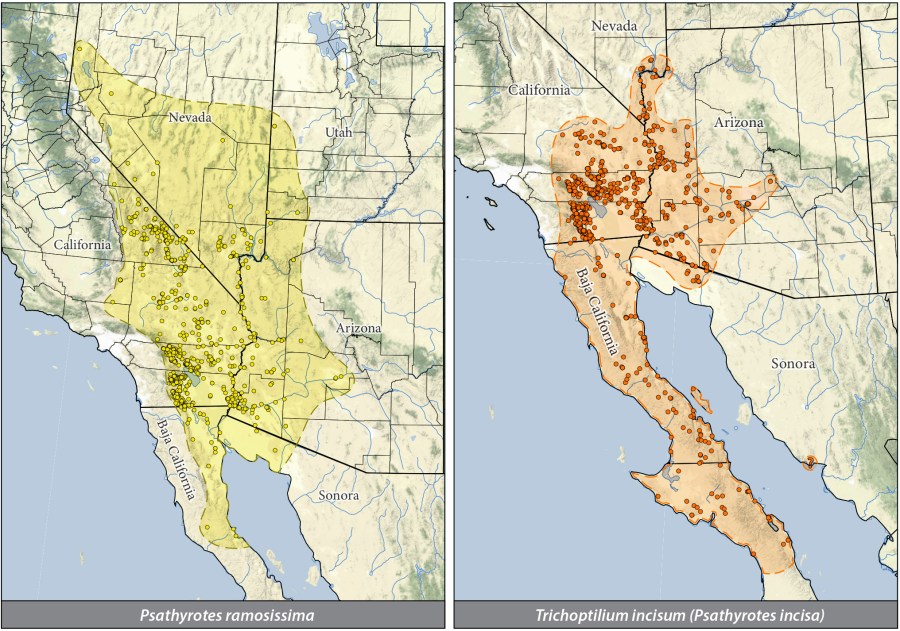

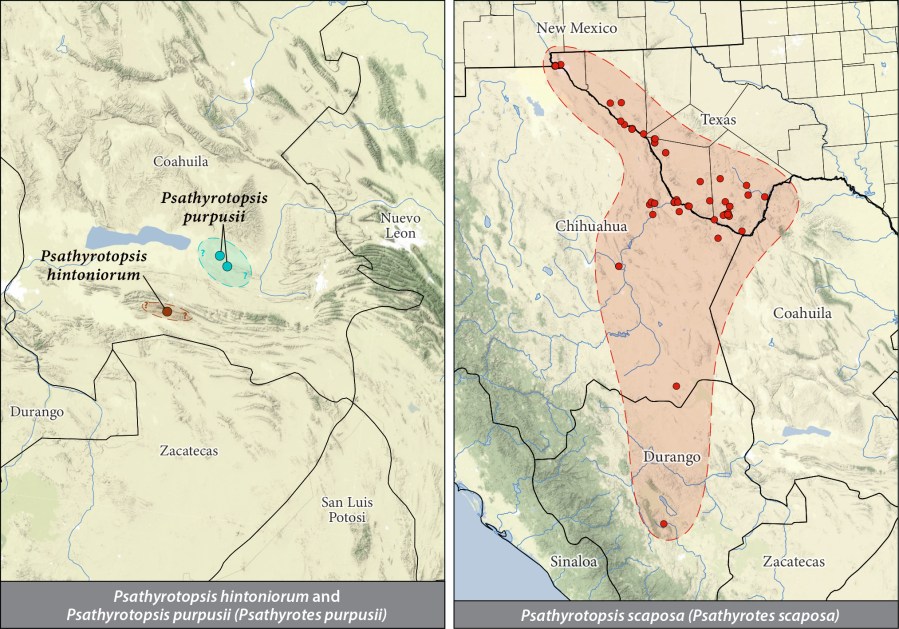

And here are maps showing the known distribution of each species, produced (by me) using QGIS and Adobe Illustrator, based on occurrence data (the dots) from specimen locations served by the SEINet Portal Network and “Research Grade” observations from iNaturalist (note: some dots could be mismapped or misidentifications). Colored shading shows the approximate generalized distribution of each taxon.

References:

Baldwin, Bruce G. 2012. adapted from Strother (2006), Psathyrotes, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.) Jepson eFlora, https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?tid=571, accessed on November 28, 2022.

Strother, John L., 2006a. Psathyrotes in Flora of North America 21:416–418 (http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=126897), accessed on November 28, 2022

Strother, John L., 2006b. Psathyrotopsis in Flora of North America 21:364–365 (http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=126898), accessed on November 28, 2022.

Strother, John L and George Pilz. 1975. “TAXONOMY OF PSATHYROTES (COMPOSITAE: SENECIONEAE).” Madroño; a West American journal of botany 23, 24–40. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/partpdf/169365

Turner, B. L. 1993. “A new species of Psathyrotopsis (Asteraceae, Helenieae) from Coahuila, México.” Phytologia 75, 143–146. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.part.17305.

Copyright © Tim Messick 2024. All rights reserved.